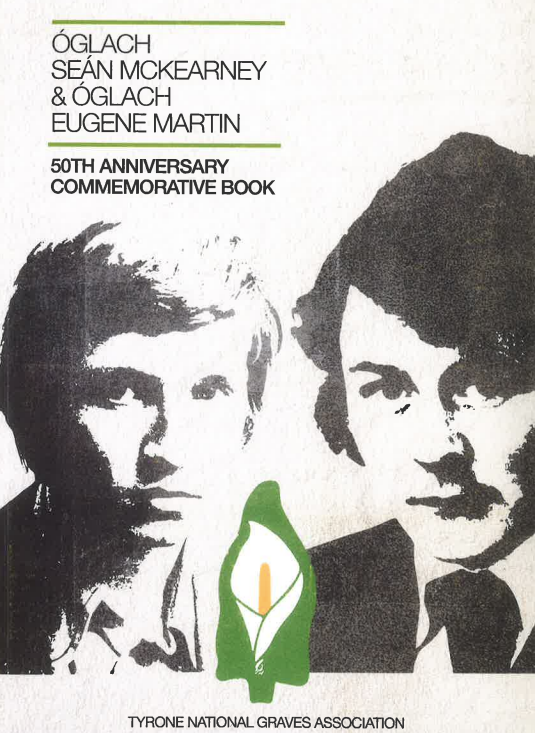

This artcile comes from the commemorative booklet for two Volunteers who died in active service fifty years ago – Séan McKearney & Eugene Martin

Tony Benn remarked not long after the collapse of the Berlin Wall that ‘there is a British problem in Ireland. There is not an Irish problem in the UK.’ Long since consigned to the backbenches, Benn attributed the British Army’s occupation of the Six Counties to the exigencies of strategic defence. He was correct. As the British state pushed the Partition Bill through parliament in 1920, the arch-imperialist, anti-Irish bigot and Tory leader, Bonar Law, argued that anyone who supported Irish self-determination was ‘living in the world with his eyes shut.’ Law further lamented the ‘childish mistake’ of ignoring Ireland’s centrality ‘to national security.’ In short, self-determination for imperial possessions had ‘never been adopted by any nation in the history of the world except after defeat and under compulsion.’[1] Those who struggled to achieve Irish freedom have been consistently characterised as an irrational, criminal tendency intent on subverting good British government and the rule of law. As James Connolly said of Wolfe Tone on the anniversary of the 1798 Revolution – ‘Apostles of Freedom are ever idolised when dead but crucified when living.’[2]

Yet, since Connolly penned those lines and gave his own life for the cause of Ireland and Labour in 1916, the establishments on both side of the British-imposed border have sought to dismiss, denigrate, and demonise Irish republicans. In short, they have promoted the British version of ‘the Irish problem.’ In the 1930s, the effective joint founder of the Revisionist school of Irish historiography, T.W. Moody, opened his study of the Ulster Plantation thus: ‘Throughout the reign of Elizabeth, Ulster had been a thorn in the side of the English government.’ As Gerard Farrell argues, this apparently commonplace assertion, from a historian who extolled the virtues of ‘value-free history’ ignores the fact that ‘the opposite might surely be claimed with (at the very least) equal truth.’[3] The conquest and plantation of the area which became East Tyrone, four hundred years ago, involved genocidal colonial violence, ethnic cleansing, and post-facto apartheid.[4] The area represented the laboratory for subsequent British colonial practice.

Colonialism is a process, not an event. This enormous, and largely unacknowledged, structural violence formed the context for modern history in the area. On 23 May 1916, the RIC in Tyrone commented that:

perhaps in no other county in Ireland had stronger or more insidious influences been at work than in this county, since the outbreak of the War, to undermine the loyalty of the people and spread the insurrectionary movement. A principal reason why strenuous efforts were made to form this county into a centre of disaffection was the historic associations of Tyrone. It was the county of the O’Neills, who were so long the irreconcilable opponents of British rule in Ireland, and it was also ‘the cradle of the Volunteer movement’.[5]

In fact, in Armagh and Tyrone, the eruption and eventual elite manipulation of sectarian violence meant that the ‘myth that the Volunteers were precursors of modern Irish nationalism has obscured the reality that to contemporary Catholics they more closely resembled the “B” Specials than a nationalist movement.’[6] For instance, on 1 May 1788, the agrarian secret society, the Defenders, publicly paraded from Blackwatertown to the Moy. This resulted in the formation of violently Protestant Volunteer corps at Benburb, Tandragee and Armagh – precursors of the reactionary Orange Order.[7] These Defenders would enlist en masse into the United Irishmen, a movement led by radical Presbyterians from Belfast, Antrim and Down. Prior to the 1798 Rising, Thomas Knox, scion of the Ranfurly family of Dungannon, famously related how the Protestant Ascendancy subverted this democratic Irish republican challenge – not for the last time, by beating the Orange drum. With the Orangemen, he opined, ‘we have a rather difficult card to play’, yet ‘on them we must rely for the preservation of our lives and properties should critical times occur’. His brother, while recognising ‘their licentiousness’ claimed that the Orangemen ‘are the only barrier we have against the United Irishmen’.[8]

Thus, a pattern emerged of the British elite coopting elements of the local Protestant community by deploying a reactionary supremacism to preserve its strategic interests against the moral claim for reconquest and decolonisation as expressed in popular Irish republicanism. We have already alluded to the 1916 Rising, but, as Connolly predicted when partition was first floated in March 1914, the unsuccessful Irish revolution ended in a carnival of reaction on both sides of the British imposed border. Again, local Irish republicans fought in defence of the Republic and the East Tyrone Brigade maintained its allegiance, unlike many other northern Volunteers who fell for Free State empty promises. The way the fledgeling ‘Free State’ prosecuted its dirty war against republicans offers a necessary corrective to the old revisionist line that the southern civil war represented an existential struggle between Treatyite ‘democrats’ and IRA ‘dictators’ or, indeed, similar propaganda from current Free State politicians about the difference between the ‘Good Old’ IRA and the norther sectarian killers and gangsters of the 1970s and 1980s. As Tom Barry rightly remarked: ‘I am not one of these who believe that war is a glorious thing… The First World War taught me that. And there is nothing romantic about war. The only war that I can justify to myself, is a war of liberation.’[9] Above all, so much of the commentary on the Irish revolution and subsequent Troubles ignores the historical reality that the nationalist population of the North, both proportionately and historically, represented the primary victims of the counter revolution.

In May 1920, the leading Orangeman Henry Stronge wrote anxiously from Tynan Abbey that ‘I don’t look forward to governing Carrickmore, Crossmaglen and other districts of “Northern Ireland” with sedition organised over the border & little or no support from England.’[10] These areas contained working-class republican communities instilled with the Fenians’ ‘democratic social ideal’.[11] These republicans, the descendants of the United Irishmen and Defenders, exhibited a non-deferential character and anti-clerical mentalité across two centuries. Tom Clarke, the architect of the 1916 Rising, joined the IRB in Dungannon. These were no mere nationalists with guns but a conscious community who challenged the Catholic pubocracy in the same breath as they damned the Protestant Ascendancy. Neither were they insular backwoodsmen, their democratic networks spanned the USA’s northeast seaboard, permeated the western tip of Scotland’s central belt and ran through the diaspora in Liverpool, Manchester and London. In 1906, Patrick McCartan expressed his exasperation with clerical condemnation of his efforts to spread republicanism in Carrickmore to fellow Carmen man and the head of the Clan na Gael, Joe McGarrity: ‘Wouldn’t an act like that make you curse the day you left a free country?’[12] Whether the dictation came from the police, the pulpit, or the parliament, across multiple generations, Fenianism survived in Tyrone.

Despite propaganda emanating from Whitehall and echoed in Dublin 4, as two young IRA volunteers died when their own bomb exploded on the way from the Moy to Dungannon in May 1974, they were not engaged in a criminal conspiracy, nor was their activism motivated by greed or financial gain. Rather Eugene Martin and Sean McKearney gave their lives in another phase in their community’s struggle against British rule and oppression – or the ‘legalised lawlessness’ exhaustively detailed by Caroline Elkins in her study of the British Empire. The 1978 Glover Report demonstrated clearly that British Army did not believe its own lies about the IRA: ‘the calibre of rank-and-file terrorists does not support the view that they are mindless hooligans drawn from the unemployed and the unemployable.’ Rather, ‘the bulk of them were young men and women without criminal records in the ordinary sense’ who appeared ‘reasonably representative of the working-class community of which they form a substantial part [and] do not fit the stereotype of criminality which the authorities have from time to time attempted to attach to them.’ Glover might have argued that in the ten years since the British Army’s introduction to the North, an experience of state repression or attacks by loyalists marked the most widespread shared feature of post-1969 IRA recruits.[13] Here, for anyone with a mind to see them, were Wolfe Tone’s Men and Women of No Property under changed historical conditions.

Yet the media and, indeed, academic history portrayed IRA Volunteers during the Troubles as irrational, sectarian fanatics, unreconstructed gangsters – or both. For instance, the doyen of revisionism, Roy Foster argued that Irish republicanism was inherently ‘Anglophobic and anti-Protestant, subscribing to the theory of the “Celtic Race” that denied the “true” Irishness of Irish Protestants and Ulster Unionists.’[14] Elsewhere, he claimed that ‘the hero cults of 1916 led to the carnage in Northern Ireland.’[15] John Regan highlights how such analysis conveniently ignores that such ‘cults pre-dated the Troubles’ and had ‘attracted little support’. Rather ‘the collision of the radicalising 1960s with Northern Ireland’s structural inequalities… mobilised (and later paramilitarised) northern nationalism – not a memory of Pearse.’[16] To understand why young Irish men and women took up the republican struggle during the northern conflict, it is necessary to address the long- and short-term historical factors, which convinced ordinary people that no alternative existed to armed conflict.

The analysis should begin with the structural violence locked into the one-party Unionist regime artificially carved out during the counter revolution. Lord Paul Bewargued that ‘there is nothing inherently reactionary about…a national frontier which puts Protestants in numerical majority.’[17] Like claims in the Southern United States that Jim Crow did not rely on overtly racist legislation, to accept this argument, one must ignore the worldview and intentions of those who imposed the gerrymandered six-county border, how they achieved it and the nature of the one-party regime that emerged as a result. Nowhere else in Ireland were civilians (mostly Catholics) murdered with such impunity as in the North, especially Belfast. A century ago, the British imposed partition in Ireland and presented supremacist Orangesim with its own corrupt and decrepit bailiwick, built in 1920 through mass work-place expulsions in Belfast approaching 10,000 Catholics and Protestant socialists, the forced removal of 24,000 from their homes, including ethnic cleansing in pockets of Belfast, and nearly the enter Catholic populations of Lisburn, Banbridge and Dromore.

Yet, Article XII of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty anticipated the creation of a Boundary Commission, which would redraw the border ‘in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions.’ Lloyd George convinced Collins and Griffith that majority nationalist Tyrone would not remain long under Unionist rule. Like innumerable cases across British imperial history – this represented a callous lie. When the Boundary Commission collapsed in December 1925, the Free State sold northern nationalists down the river. In the intervening period, Craig’s government consolidated its control over Tyrone, establishing the Leech Commission, which gerrymandered electoral boundaries, abolishing PR, and inserting a rateable valuation clause in the Local Government Act (1922), thereby guaranteeing control of the county council and local bodies, and the crucial patronage that went with them.[18]

By 1969, the Cameron Commission reported that across majority nationalist areas, Unionists had consistently manipulated electoral boundaries to control local government and then ‘use their power to make appointments in a way which benefited Protestants’ in housing and employment.[19] As the Partition Act passed through parliament, the British government also sanctioned the creation of the Ulster Special Constabulary [USC], a paramilitary police force for the new jurisdiction.[20] In September 1920, Tyrone’s three UVF commanders: Ambroise Ricardo, Robert Stevenson and John McClintock, assured the rank and file that the USC represented Carson’s Army reincarnate.[21]

Above all, Unionist claims to Tyrone rested on force, that might is right, a viewpoint which successive politicians articulated as such. On 15 March 1922, Dawson Bates introduced the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Bill, which permitted search, arrest, and detention without warrant, flogging and capital punishment for arms offences and the total suspension of civil liberties. The British government then funded the Specials to the tune of £6 million during a global post-war recession to shore up this discriminatory statelet. Not for the last time would local Protestants learn that loyalty to the Crown and the value of the half-crown enjoyed a symbiotic relationship! By 1924, England and Wales had one police officer for 699 people, Scotland one for 751, while, under Unionist rule, the ratio sat at one for every 160 inhabitants.[22] In 1925, one Liberal MP wryly pointed out that James Craig wielded an armed force larger than the armies of Austria or Bulgaria.[23] These Specials formed their own branches of the KKK in Belfast and Tyrone and in the 1930s James Craig claimed that the ‘Orange Order, the Black Brotherhood or the B Specials could substitute as Fascists.’[24]

This blizzard of sectarian doggerel, epitomized by Basil Brooke’s admonition not to have a Fenian about the place, emerged from Unionist anxiety in the wake of working-class solidarity during the 1932 Outdoor relief Strikes. That year, the parliament at Stormont opened to a cost of £1.7 million while [150 million in today’s money] while 27 per cent of the population were unemployed [the rate amongst Catholics was nearly half]. Unionist politicians responded by reinforcing the punitive Poor Law and setting relief well below the level available in Britain. Faced with the unemployed masses on the Falls and the Shankill co-operating, the Unionist reflex mirrored that of the 1790s and 1920 – bang the drum.

For four decades from Craig through Andrews and onto Basil Brooke, reactionary bigots led Ulster Unionism. By 1933, Andrews challenged those who claimed that Catholic porters outnumbered Protestants at Stormont’s recently opened parliament buildings, adding ‘I have investigated the matter, and I find that there are 30 Protestants, and only one Roman Catholic there temporarily.’[25] When, that very year, Basil Brooke told assembled Orangemen at the Twelfth Field that he hadn’t a Roman Catholic about his own place, Craig subsequently supported him at Stormont and claimed that ‘there is not one of my colleagues who does not entirely agree with him.‘[26] Indeed, the following month, he notoriously told the same body that ‘I am an Orangeman first and a politician and Member of this Parliament afterwards’ and that Stormont was a ‘Protestant Parliament and Protestant State.’[27] In short, the Orange social contract underpinning North’s foundation and continued miserable existence required a material basis in discrimination.

Yet, Ulster Unionism’s determination to retain majority nationalist areas like East Tyrone within Craig’s impregnable Six-County Pale and the Orange populist character of its discriminatory rule created the long-term conditions for its eventual demise a half century later. On 24 August 1968, the first civil rights set out from Coalisland to Dungannon, when the republican community engaged in one of those small acts, which, when multiplied, can transform the world.[28] A young Bernadette Devlin joined the march from ‘90% Republican’ Coalisland, which descended from a carnival atmosphere to one of ‘passive anger’ when an RUC cordon blocked the marchers’ entry into Dungannon. Afterwards in a Coalisland pub, Devlin criticised ‘out of touch’ middle-class constitutional politicians who ‘thought they could come down, make big speeches, and be listened to respectfully’. It was then that ‘the people all got out together’ and ‘turned round and said in effect to the politicians, ‘Clear off, you don’t even think the way we think.’[29]

The Civil Rights’ movement that emerged in the 1960’s represented a challenge to fifty years of institutionalised discrimination, but the notion that Britain now somehow fulfilled the role of frustrated referee flies in the face of evidence. The British Army carried out the Falls Road curfew less than a year after the pogrom against Belfast’s Catholics in August 1969. They were the hammer in Faulkner’s hand during internment the following August, when only nationalists suffered internment and many endured torture. In short, Ted Heath’s government handed the army over to a one-party discriminatory regime to restore order. Order represented the implementation of Frank Kitson’s counter-insurgency strategy, developed in Malaysia, Cyprus, Aden, and other exotic relics of Britannia’s empire. The Army ‘got tough’ by imposing curfews and terrorising entire working-class nationalist areas, interning and torturing hundreds of young nationalist men, and indiscriminately killing nationalist civilians – the Paratroop Regiment alone responsible for twenty-five such killings through the Ballymurphy Massacre in August 1971 and Bloody Sunday in Derry in January 1972. When Maudling lied to parliament after Bloody Sunday, he merely confirmed the lesson of history that Britain’s murderous mendacity knew no limits.

Under intense international pressure, Heath suspended Stormont, but this did not stop the military carrying out a proxy war against Catholic civilians through loyalist paramilitaries, including the thirty thousand strong UDA, which Britain refused to declare illegal. After Eugene and Seán’s deaths, the British would implement a three-pronged strategy of Criminalization, Ulsterization and Normaliszation. The first aspect involved the suspension of trial by jury, a conveyor belt of convictions through Diplock courts, typically secured on the strength of confessions extracted under torture. Those convicted then found themselves in the H Blocks, the most expensive and secure prison in western Europe. Engels identified an earlier manifestation of this tendency when the British hung three Fenians in Manchester in 1869, comparing it to the abolitionist, John Brown’s, execution in 1859, with the important caveat that ‘the Southerners had at least the decency to treat J. Brown as a rebel, whereas here everything is being done to transform a political attempt into a common crime’.[30] Thatcher’s determination to demonstrate to the world that crime is crime is crime culminated in the death of ten hunger strikers in pursuit of special category status that the British government had previously granted.

Yet the way Britain dealt with republican violence only tells half the story. The evidence clearly indicates that republicans killed more people (58.6%) than any other tendency in the conflict. Nevertheless, the two largest groupings killed in the Troubles were Catholic civilians and members of the security forces.[31] Clearly, if one examines the facts, it becomes clear that ‘Catholic civilians have evidently suffered both absolutely and relatively more than Protestant civilians.’[32] While the PIRA carried out atrocities, almost two-thirds of its fatalities constituted combatants. The British killed more civilians than combatants and almost ninety per cent of loyalist killings represented Catholics or Protestant civilians killed in error. In terms of actual people, the security forces killed almost two hundred civilians, loyalist over 880 and republicans over 720 civilians.[33] This violence operated within a context wherein ‘the British and loyalist campaigns were symmetrical’ and ‘the Protestant murder gangs helped wear the Catholic working class down.’[34] Recent allegations that Robin ‘the jackal’ Jackson and Billy ‘king rat’ Wright were agents of the crown come as no surprise to those who lived in the murder triangle.

There seems little doubt now that systemic collusion existed between the British state and loyalist paramilitaries. The de Silva report established that security forces produced 85 per cent of all UDA intelligence information by the time they shot Pat Finuance in 1989. The Stevens investigation into collusion arrested 210 loyalist paramilitary suspects, only three of whom were not state informers. Clearly, ‘instead of being the least-worst option… many within government and the security forces, given their convergence of aims and objectives’ promoted collusion ‘to defeat the IRA and maintain the union. Britain was never a neutral broker.’[35] Rather than the two warring tribes’ narrative emanating from Whitehall, which academia in general do service to, in terms of actual events, there is a far more compelling case to be made that ‘London’s top priority has always been to portray itself internationally as an honest broker between two rival, incomprehensible and irrational religious tribes.’ Within this context, collusion helped ‘to lower nationalist aspirations and persuade the Catholic community to abandon both the political aims and methods of the IRA. If the British carrot held out to the Catholic/nationalist community was the promise of increased political influence, including a possible consultative role for Dublin, then the existence of a loyalist stick was a useful tool in its box – so long as it had gloves to keep its hands clean.’[36]

In fact, the British state consistently underpinned the material basis of reactionary Orangeism throughout the conflict. In the short to medium-term, the Troubles cemented the sectarian differential through deliberate British policy. After the implementation of Ulsterization in 1976 (the decision to, where possible, pull back British Troops and effectively sectarianise the conflict in line with propaganda) the RUC and UDR had 20,000 members and with the inclusion of prison officers 30,000 Protestants gained state employment directly linked to the conflict. By 1981, one in ten Protestant men worked for the security forces.

Therefore, after over a decade of conflict, while both working classes suffered widespread poverty and insecurity, Catholics experienced considerably more. Catholic unemployment remained several times greater than the British average and well above the worst-hit black spots. Indeed, it considerably outstripped unemployment amongst any disadvantaged ethnic minority in Britain or western Europe for that matter. Indeed, even employed Catholics crowded into low-paid, insecure jobs. On the other hand, Protestant unemployment rested only slightly above the British average and considerably lower than post-industrial periphery of northern England, Scotland, and Wales. In effect, state subsidy kept Protestant male unemployment ‘artificially low’ during a recession due to ‘the provision of thousands of jobs in the RUC, UDR and other security-related occupations.’[37]

Irish republicans have every right to commemorate their dead. This is not a celebration of violence, nor is it intended as an insult to their victims. The historical reality is that, over four centuries, the ‘legalised lawlessness’ of British rule in Tyrone has carried out far more violence than those intent on Irish freedom. The historical reality is that while the United Irishmen, the Fenians, and every iteration of the IRA, surely inflicted suffering and, indeed, engaged in at least ‘functional sectarianism’ and occasionally explicitly sectarian violence, the weight of sectarianism and anti-democratic violence lay overwhelming on the side of Britain and its proxies.[38] The Unionist one-party regime established by ethnic violence in the North and cemented by reactionary Free State violence under the British threat of terrible war in the South has always represented an affront to democracy. Loyalism, the apparent eternal plaything of Unionist grandees and British statesmen has always denied its cherished ‘civil and religious liberties’ to Irish Catholics. The men and women of no property who took up the struggle in Tyrone during the Troubles did not do so out of any inherent hatred of their neighbours or irrational propensity for violence. They did so to right an historical wrong, to assert the legitimacy of their own community and because the forces railed against them left them little choice but to lie down or stand on their own feet – these Croppies did not lie down.

[1] Hansard, House of Commons, 30 March 1920, Vol 127, c 1125-6.

[2] Workers’ Republic, 13 August 1898.

[3] Gerard Farrell, The ‘Mere Irish’ and the Colonisation of Ulster, 1570–1641 (2017), p. 9

[4] See James O’Neill, The Nine Years War, 1593–1603: O’Neill, Mountjoy and the military revolution (Dublin, 2017).

[5] F. X. Martin, ‘The McCartan Documents, 1916’ in Clogher Record, Vol. 6, No. 1 (1966), p. 5.

[6] D.W. Miller, ‘The Armagh troubles 1785-1795’ in S. Clark and J.S. Donnelly (eds.), Irish peasants, violence and political unrest, 1780-1914 (Wisconsin 1983), p. 187

[7] Jim Smyth, The Men of No Property: Irish Radicals and Popular Politics in the Late Eighteenth Century (Dublin, 1998), p. 49.

[8] Whelan, The Tree of Liberty (Cork, 1996), p. 119.

[9] Barry quoted in Kenneth Griffith and Timothy O’Grady, Curious Journey; An Oral History of Ireland’s unfinished revolution (Cork, 1998), p. 143.

[10] Stronge to Montgomery, 30 May 1920 (PRONI, D627/435/94).

[11] Owen McGee, The IRB: The Irish Republican Brotherhood, from the Land League to Sinn Fein (Dublin, 2007).

[12] Patrick McCartan to Joseph McGarrity 21 January 1906 (NLI, McGarrity papers, P8186).

[13] Quoted in Brendan O’Leary, A Treatise on Northern Ireland: Volume One – Colonialism (Oxford, 2019), p. 58.

[14] Roy Foster, Modern Ireland (Penguin, 1990), p. 459

[15] This is quote from R. Foster, ‘History and the Irish Question’ in Paddy and Mr Punch (London, 1993), p. 17.

[16] Regan, ‘Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’, p. 12; ‘this observation again invites other causal explanations for the reappearance of militarist-republicanism. Unsurprisingly, these identify rising expectations among Northern Ireland’s Roman Catholic minority amid the radicalizing international tumult of the 1960s, and the inability of Unionist governments to introduce reforms while containing growing unrest’, in John Regan, ‘The O’Brien ethic as an interpretative problem’, in Myth and the Irish State.

[17] Bew, Gibbon & Patterson, The State in Northern Ireland (Manchester, 1978), p. 221.

[18] Paul Murray, The Irish Boundary Commission and its origins, 1886-1925 (Dublin, 2011), 314.

[19] Disturbances in Northern Ireland (Belfast, 1969), Paragraph 138.

[20] Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants (London, 1983), 43-4.

[21] Highly confidential Memoranda, September 1920 (PRONI, Newton family papers, D1678/6/1).

[22] Graham Ellison and Jim Smyth, The Crowned Harp: policing in Northern Ireland (2000), pp 19-20.

[23] Hansard, House of Commons, 23 February 1925, vol. 180, cc. 1651-1686.

[24] James Loughlin, ‘Northern Ireland and British fascism in the inter-war years’, in Irish Historical Studies 29, 116, (1995), p. 544.

[25] David McKittrick & David McVea, Making Sense of the Troubles: A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict (London, 2002), 15.

[26] Sir James Craig, Unionist Party, then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, 20 March 1934.

Reported in: Parliamentary Debates, Northern Ireland House of Commons, Vol. XVI, Cols. 617-618.

[27] Sir James Craig, Unionist Party, then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, 24 April 1934

Reported in: Parliamentary Debates, Northern Ireland House of Commons, Vol. XVI, Cols. 1091-95.

[28] The phrase is Howard Zinn’s.

[29] Bernadette Devlin, The Price of My Soul, (New York, 1969), pp 94-6.

[30] Engels to Marx, 24 Nov. 1867.

[31] David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney and Chris Thornton, Lost Lives (2007)

[32] Brendan O’Leary and John McGarry, The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland (London, 1996), p.34.

[33] Marie Therese Fay, Mike Morrissey and Marie Smyth, Mapping Troubles-Related Deaths in Northern Ireland 1969-1998, INCORE (University of Ulster & The United Nations University)

[34] John Newsinger, British counterinsurgency

[35] Anne Cadwallader, Lethal Allies, p. 363.

[36] Ibid, p. 360.

[37] B. Rowthorn and N. Wayne, Northern Ireland: The Political Economy of Conflict (Polity, Cambridge, 1988), conclusion.

[38] ‘Functional sectarianism’ is from Matthew Lewis and Shaun McDaid, ‘Bosnia on the Border,’ in Terrorism and political violence, 24:2 (2017) pp 635-55.

Leave a comment